T E Kinsey

Tim Kinsey was born in England in the mid-1960s when everything was groovy. He grew up in London in the ’70s when everything was brown and mostly made of corduroy. He went to university in Bristol in the 1980s when hair was big and spectacles bigger. He worked in magazines in the ’90s when Britannia was cool. In the early-2000s, when the millennium was new and the possibilities boundless, he helped the Internet to boom by working on one of its most famous sites.

And now he writes murder mysteries.

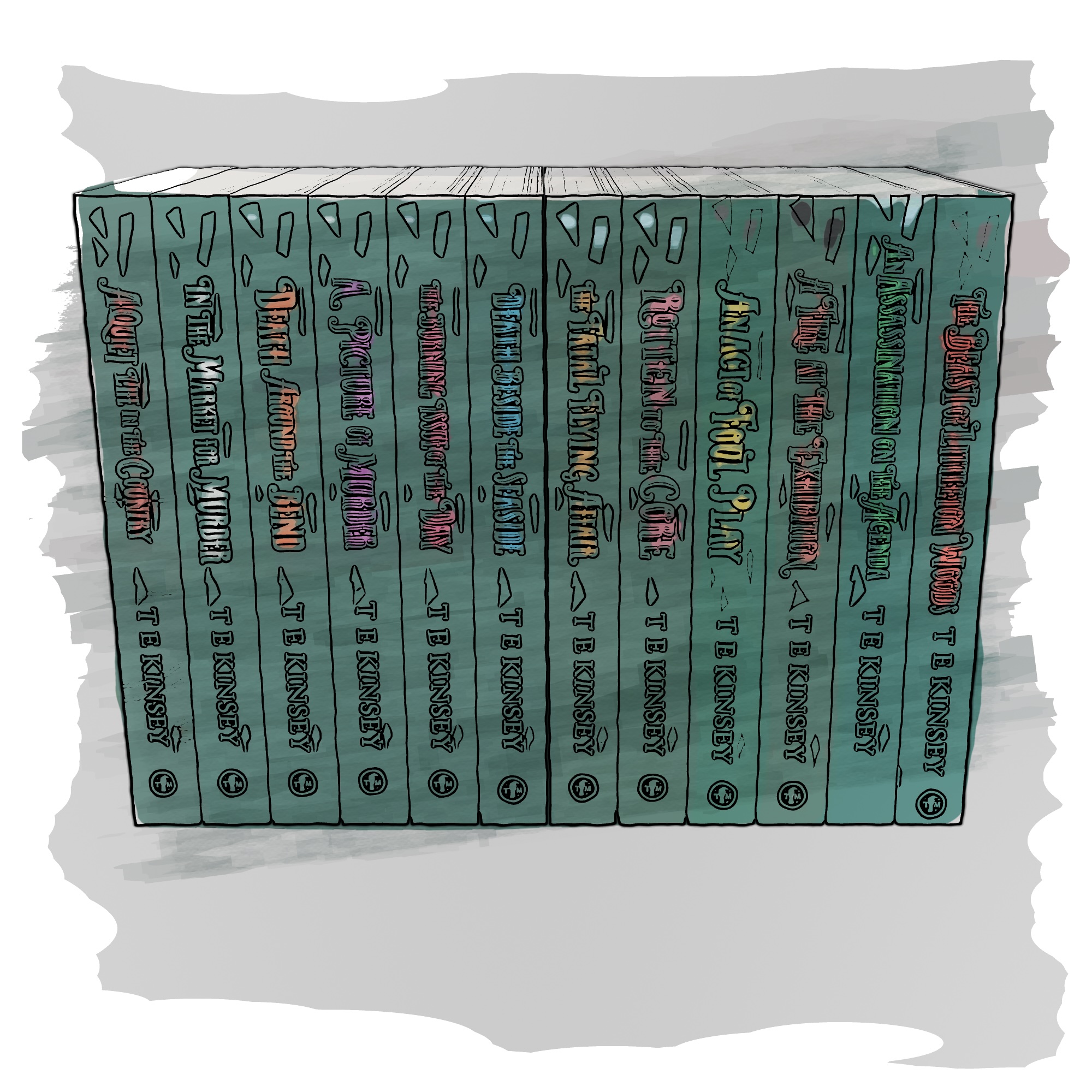

Lady Hardcastle first appeared in October 2014 in four short stories gathered together in a self-published version of A Quiet Life in the Country. In July 2015 four more stories appeared as The Spirit Is Willing. At the end of that year he signed a publishing deal with Thomas & Mercer.

An edited (restructured) version of A Quiet Life in the Country was published by Thomas and Mercer in October 2016, closely followed in December by a similiarly restructured version of The Spirit Is Willing, now retitled In the Market for Murder. The third book in the series, Death Around the Bend, appeared in June 2017.

Book 4 was delayed by “certain things” and so he wrote a short, Christmas-themed story to bridge the gap. Christmas at The Grange was published as a Kindle Single in December 2017. Although it was published soon after Death Around the Bend, the events take place after the fourth book, A Picture of Murder, which was published in October 2018. Book 5, The Burning Issue of the Day came along a few months later in April 2019, quickly followed by Death Beside the Seaside in October 2019. The Fatal Flying Affair saw our heroines take to the air in December 2020 and then a new, spin-off series began in 2021 with The Deadly Mysery of the Missing Diamonds in March and A Baffling Murder at the Midsummer Ball in July.

Lady Hardcastle returned in June 2022 with Rotten to the Core, with An Act of Foul Play following just a few months later in November 2022.

September 2023 saw the arrival of A Fire at the Exhibition, followed by An Assassination on the Agenda in May 2024 and The Beast of Littleton Woods in May 2025.

Tim lives just outside Bristol with his wife, a drum kit, five guitars and more Lego than an adult should own. He used to own two drum kits but . . . but that’s a long, boring story about drum kits. tl;dr: there’s just one now. The couple’s three children have long since been encouraged to leave home, ostensibly to enable them to make lives for themselves, but mostly to make more room for drum kits, guitars, and Lego.

Lady Hardcastle

The briefest of biographies

Emily, Lady Hardcastle, was born Emily Charlotte Ariadne Featherstonhaugh (pronounced Fanshaw) on 7 November 1867. She was the younger of the two children of Sir Percival Featherstonhaugh, Permanent Secretary to the Treasury, and his wife Ariadne, known to her friends — of whom there were many — as Addie.

She and her older brother Henry Alfred Percival Featherstonhaugh – who had never been anything other than Harry – had an almost idyllic childhood. There were toys, and outings, and friends who came to tea. When their parents entertained, the two children would sneak to the top of the stairs where they would almost always be “accidentally” caught and indulgently introduced to the guests by their doting parents. For five years, Emily’s life had been idyllic, and then one day, it had come crashing down around her ears. Harry, now aged seven, was sent away to school.

Emily was devastated. Not only had her childhood companion and confederate been taken from her, but he was off on an extra special adventure that she couldn’t share. He had gone to school. He was going to be learning things that she felt she would never be allowed to know. It just wasn’t fair.

She had made such a fuss that her parents, as indulgent as ever, had engaged a governess several years before they had planned and Emily, determined to prove herself every bit as clever as her brother, had taken to her lessons with a determination that surprised everyone. It wasn’t long before the first governess, whose specialism had been teaching simple reading and arithmetic skills to the very young, was forced to admit that the young girl had long since passed the level at which she felt comfortable teaching, and another had to be engaged. And then another. And another.

The years passed and Emily’s academic prowess showed no sign of peaking. It had been expected that she would follow her parents’ friends’ daughters who were attending an assortment of finishing schools around Europe before being presented at coming out balls and beginning the search for suitable husbands. But when Harry came home for Christmas 1883 and told her that he was about to sit the Cambridge entrance examination, Sir Percival and Lady Featherstonhaugh’s plans were changed again. Harry intended to study at their father’s old college, Kings, which meant that Emily would be unable to follow him, but there was a women’s college now, and Emily set about persuading her beleaguered parents that they should support her newfound ambition.

And so it was that in October 1884, Emily Featherstonhaugh had gone up to Girton College, Cambridge.

In A Picture of Murder we learn the story of her marriage to Roderick (later Sir Roderick) Hardcastle and their career as diplomats and spies.

Florence Armstrong

Another frustratingly brief biography

Born on 24 March 1877, the youngest – by 20 minutes – of seven children born to Joseph Armstrong and his wife Marged (whom everyone knew as Meg). Joe Armstrong was a circus knife thrower who performed as The Great Coltello, and Florence and her twin sister Gwenith were born “on the road” during the circus’s long spring and summer tour.

Meg’s mother fell ill and so Meg took the twins with her back to Aberdare in South Wales to look after her mother (whom Flo always knew as Mamgu – Welsh for grandma).

The girls attended school and left at thirteen. While Gwenith was happy to join her mother working in a local grocer’s shop, Flo wanted to see more of the world. She took a job as a scullery maid to a wealthy family in Cardiff.

An unusual relationship

Yes, but why are they like that?

My maternal grandmother was a cook in domestic service in the 1920s and ’30s. She came from Aberdare but at some point she moved to London where she met and married my grandfather.

She died of a brain tumour in 1940 when my mother was only 2 and my uncle not quite 4. There are no family stories about her – that’s pretty much all I know.

In the ’70s my mother was a big fan of Upstairs Downstairs and The Duchess of Duke Street (it took me years to figure out why she was so interested in early 20th century domestic service) and so I was exposed to them, too. My entire understanding of servants and their duties came originally from Upstairs Downstairs. When Downton Abbeystarted, I thought about it all some more.

Both shows depict (for obvious dramatic reasons) large families with a large household of servants. “Us and them” - Upstairs Downstairs even hints at that in the title. There are lots of stories to tell within each group, and lots more to tell about the interactions between the two groups. It’s a story motherlode.

But, I thought, that’s not typical. Yes, those sorts of households existed, but they were far from the norm. There would be smaller families with smaller retinues. Even, I reasoned, sometimes a single employer with a single servant. “Us and Them” would sometimes be “me and you”.

And what would their relationship be? Would the fact that they were living together in the same house day and night break down the social rules and allow them to be friends? Of course not, don’t be silly.

Ok, but what if they were put under pressure? What if circumstances arose that forced them to rely on each other not just as a payer of wages and a cooker of food, but for their very survival. Maybe not if they were men. Englishmen can be best friends for years but social taboos prevent them from ever showing affection, or even saying out loud how much they mean to each other. Women? Maybe.

So I devised a story where a young couple moves to a remote hill station in India where he runs a tea plantation and she plays the piano, paints, and tries to teach the local children to read and write English. He is happy to hire local servants, but she had insisted on taking her lady’s maid with her. The husband dies suddenly and unexpectedly (of natural causes) and the wife decides she has to return home. She regretfully dismisses the local servants and makes her own way across country to Calcutta with only her maid for company.

It’s a hard journey, beset with difficulties, and slowly the two women become actual friends. The social barriers that ought to keep them apart begin to seem absurd. By the time they return to England they’re talking to each other as equals. Some problems, obviously, ensue.

It all seemed like a splendid idea, but it also seemed like a properly grown-up novel of the sort that I’m not in the least bit qualified to write. I mostly do glib and flippant. I put the characters and the idea to one side.

When I came to write a murder mystery, I realized I already had a detective and sidekick on the character shelf, fully developed and ready to go. I tweaked the back story to put them in China (mostly so that Flo could learn martial arts – something I still find funny). I made Sir Roderick a diplomat rather than a tea planter, and his wife a spy rather than a teacher. I had him murdered by foreign agents rather than dying of a fever. But the way that the relationship between Lady Hardcastle and Flo came about was essentially the same. They escaped, mostly alone, across China. They’ve been through extraordinary things together and class distinction doesn’t mean a great deal to them any more.

The Circus Comes to Town

What happened to the circus story?

In In the Market for Murder, Lady Hardcastle mentions some ‘murder and mayhem’ they had experienced at the circus the previous autumn. The conversation seems to indicate that the reader might have missed an important instalment of their adventures.

You haven’t.

I originally wrote A Quiet Life in the Country in 2014 for my own entertainment. It was a collection of four separate mysteries: ‘The Body in the Woods’, ‘The Circus Comes to Town’, ‘The Case of the Missing Case’, and ‘The Half Death of Günther Ehrlichmann’.

I self-published the book through Kindle Direct Publishing (and later in paperback through CreateSpace) in October 2014.

I followed that up with The Spirit Is Willing in July 2015. Again it was four mysteries: ‘The Farmer’s Revenge’, ‘The Ghost of the Dog and Duck’, ‘The Trophy Case Case’, and ‘The Last Tram’.

At the end of 2015 I was approached by Thomas & Mercer. They wanted to offer me a three-book publishing contract. They wanted me to re-write the two existing books so that they became novels, and to finish the third book that I was already working on (Death Around the Bend).

We worked together to try to produce the novels without losing too much of the feel of the originals. For the new version of A Quiet Life in the Country we used ‘The Body in the Woods’ as the spine of the story and dropped ‘The Case of the Missing Case’ in the middle as a set piece country house murder. By changing the villain and making them responsible for both crimes we had a more-or-less full story.

It meant we had to drop ‘The Circus Comes to Town’ and ‘The Half Death of Günther Ehrlichmann’, though. I wasn’t too bothered about the Ehrlichmann thriller story and I knew I could convey the meat of the story (Flo tells their early life stories in flashback) elsewhere. In fact it had to wait until A Picture of Murder, but I got there in the end. There was nothing to do to save ‘The Circus Comes to Town’ but it was my favourite and I didn’t want to lose it completely.

We began the same process on The Spirit Is Willing. The theme of all the stories was the same so by re-jigging the villain again we were able to mesh the first three stories to turn them into a single narrative. ‘The Last Tram’ fell casualty to the edit but I knew I could use the characters again if I wanted to (I eventually reused them in different circumstances in The Burning Issue of the Day). The new version was retitled In the Market for Murder.

I was still determined that one day I would get an opportunity to rerelease ‘The Circus Comes to Town’ so I made sure to put a reference to it into In the Market for Murder. That way the adventure had a place in the ladies’ timeline and it wouldn’t make people say, ‘No, wait, where did that fit in?’ when I eventually found the time to rejig and release it. I hoped it wouldn’t cause too much confusion (they’re always mentioning past adventures that we’ll never learn anything more about) but the downside, of course, is that people now say, ‘No, wait, I don’t know anything about the circus story.’

So you’ve not missed out on anything, and it does all make a haphazard sort of sense.